Understanding frosts and freezes by Mario Villarino

[adning id=”33097″]

Two types of cold events can damage plants in Texas: advective freezes (“freezes”) and radiative frosts (“frosts”). Texans are familiar with the term blue norther, a windy cold front that moves south from Canada through the Great Plains. The technical term for these events is advective freezes.

Advective freezes bring sudden, steep plunges in temperature, wind speeds of more than 4 mph, and masses of cold air from 500 to 5,000 feet deep. They may bring clouds and precipitation at the onset and can take 1 to 3 days to make their way out of Texas.

These freezes create uniformly cold temperatures throughout the plant canopy, sometimes damaging the plants from their lowest to highest points. The harm is caused by low temperatures and drying, sometimes relentless, winds.

Some of the most serious plant-damaging cold events recorded in Texas have been advective freezes. Most frequent in the winter, they occasionally wreak havoc in the fall as they usher in winter suddenly before the plants have time to acclimate. Freezes generally become less numerous and less severe as spring arrives, although it takes only one serious freeze late in the spring to damage tender transplants and spring-blooming fruits.

Radiative frosts occur when the sky is clear and winds are less than 4 mph. During the day, the sun’s radiation heats the plants and soil; at night, they lose radiation back to the sky. Plants and other objects cool faster when skies are clear because of the unimpeded loss of radiation.

Depending on the amount of radiation that the plants gain during the day, they may cool steadily at night to the freezing point before sunrise. This can occur on clear-sky nights in the winter, spring, or fall. On cloudy nights, the clouds reflect radiation back toward earth, which slows plant cooling and reduces frost injury.

The most severe radiative frosts occur when the weather is cloudy during the day and clear at night. The clouds reduce the amount of radiation absorbed during the day; if they dissipate late in the day or early during the night, intense cooling and plant freezing may be experienced.

Because the tops of the plants are most exposed to the open sky, they are the likeliest parts to be injured by radiative frost. The leaves at the top of the plant slow the radiation loss from the lower sections, so the cold damages the plant’s outer and upper parts most on frost nights.

Under radiative conditions, the leaves, stems, and other plant structures that have full sky exposure can be as much as 5 degrees colder than the recorded air temperature. This is why some plants show frost injury even when the recorded air temperatures did not drop below 32°F.

Radiative frosts are accompanied by temperature inversions, which occur when the ground cools quickly but no wind mixes the air, leaving layers of cold air close to the ground. Depending on the topography and inversion strength, a cold air inversion may be 50 to 150 feet deep.

[adning id=”33207″]

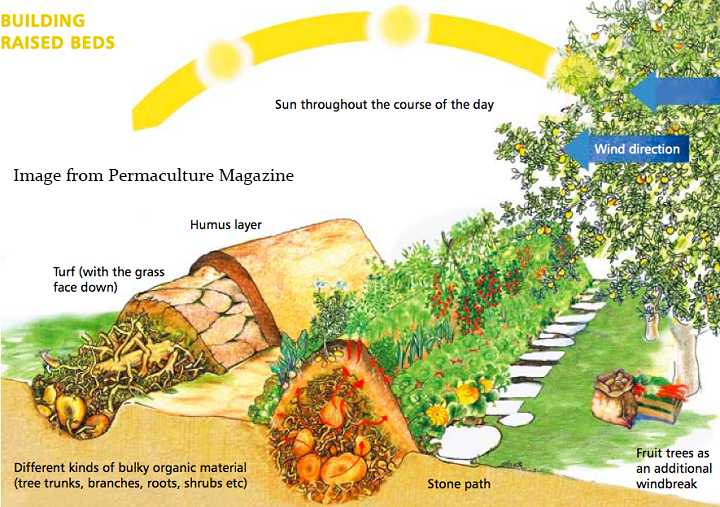

Low-lying topography is colder in radiative frosts because of the inversion and the tendency for cold air, which is heavier than warm air, to settle into “frost pockets.” Avoid planting cold-sensitive plants in frost pockets. Monitor the temperature near the ground, which can be a few degrees colder in a radiative inversion.

Radiative frosts occur often in winter and can seriously damage delicate and marginally adapted plants. They generally occur one or more nights after an advective freeze has left the region. Although fewer frosts occur in the spring, they are the ones chiefly responsible for damage to spring-blooming fruit crops or early-spring vegetable transplants.

Although a radiative frost does not last long—as little as 1 to 4 hours—the damage can be disastrous.

After a freeze or frost, the leaves of damaged herbaceous plants may immediately appear withered and water soaked. However, the freeze injury to the twigs, branches, or trunks often doesn’t appear on shrubs and trees right away. Wait a few days and then use a knife or thumbnail to scrape back the outer bark on young branches. Freeze-damaged areas will be brown beneath the bark; healthy tissues will be green or a healthy creamy color.

Delay pruning until time reveals the areas that are living and dead and until the threat of additional frosts or freezes has passed. Leaving dead limbs and foliage at the tops of plants will help protect the lower leaves and branches from nighttime radiation loss. Pruning after a freeze does not improve the outcome.

[adning id=”33207″]

Also, plants that are pruned tend to be invigorated more quickly, which may set them up for further damage in Texas’s unpredictable cycling of warm and cold temperatures.

For more information on this or any other agricultural topic please contact the Hopkins County Extension Office at 903-885-3443 or email m-villarino@tamu.edu.

Contributed by Mario Villarino

[adning id=”33207″]