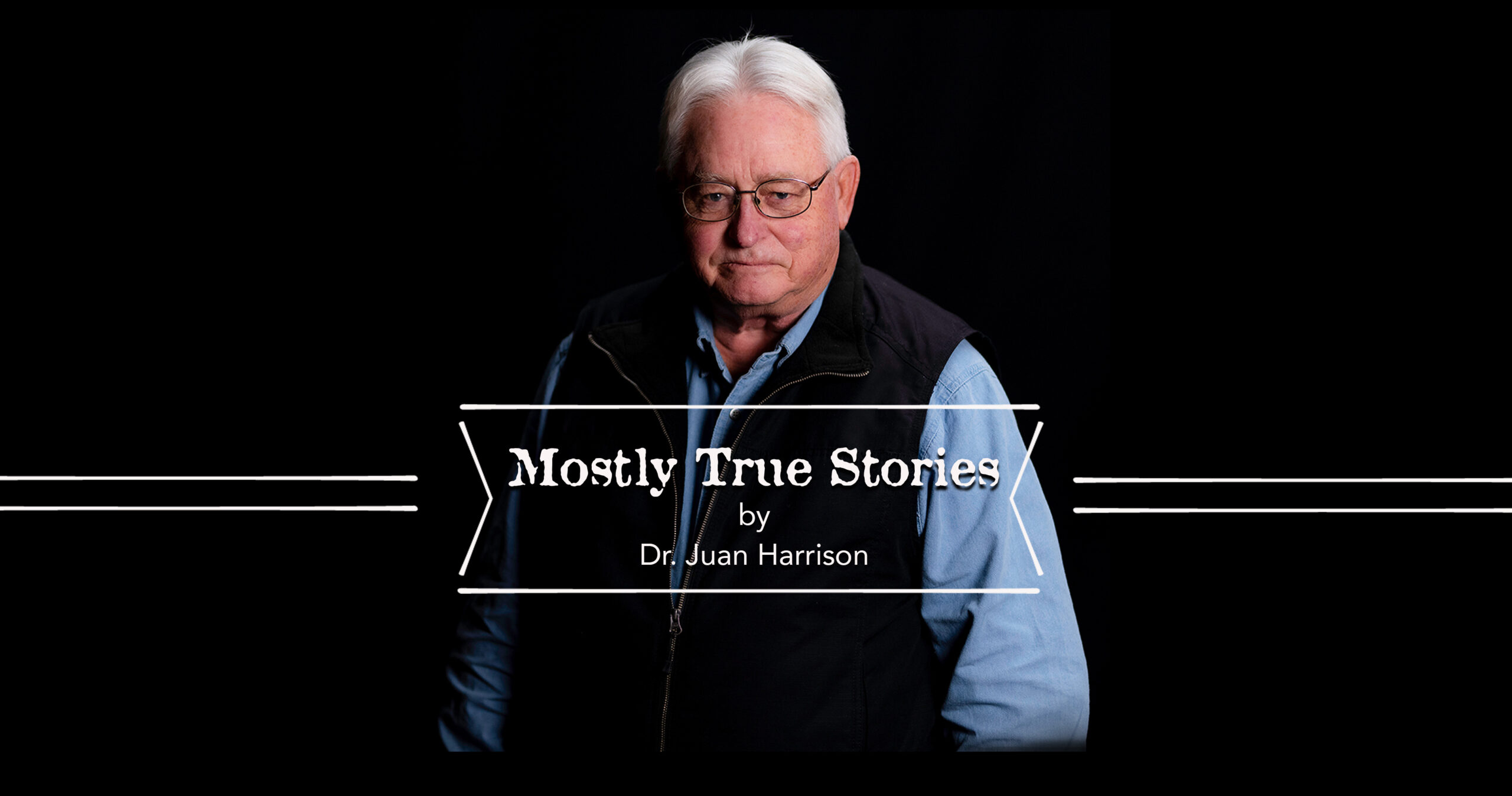

History of Confederate Refugees in Hopkins County

[adning id=”33097″]

Five miles out of town at the roadside park on State Highway 19 North, a historical marker erected in 1965 marks the spot where the Stone family of Louisiana took refuge when they fled the economic hardship and turmoil of the deep South to the relative safety of Texas during the Civil War. Although the war lasted from 1861-1865, Texas found itself torn economically and ideologically for much longer than that, and tracing the history of confederate refugees in Hopkins County leads us to examine exactly what it means to seek refuge.

The marker states:

- “The Civil War refugees family of Mrs. Amanda Stone was shown great kindness when rescued by Hopkins County people after a roadside accident that happened here.”

According to the marker, the Stone family was on their way to Birthright.

- “The Stones saw the Texans share what little they had, even to cooking the last old farm hen to feed them.”

Back as early as the start of the war, according to Hopkins County Historian June Tuck, the newly formed Confederacy had begun to levy taxes and control commodities to fund the wartime economy. Goods were bought specifically by the county government out of Huntsville, Texas, according to Tuck, and resold to local families for a slightly higher price.

This seemed to have kept local economies afloat, according to Tuck: without this commerce, “many families would have had to do without,” she wrote. Trade routes from the North were cut off. One Hopkins County trader who had gone to Michigan to buy furniture making supplies wrote home that he wished he had traveled to Saint Louis instead, as all his supplies were confiscated at the union blockade.

Prices for goods were set by the State Commissioner, and were not to exceed a certain rate. However, the county commissioner’s court had to post notices specifically to cotton growers to sell to them, as some farmers were distrustful of confederate money. In some cases the commissioner’s court directly made transactions, in one case buying 300 bales of cotton and giving it to the wives of confederate soldiers. It comes as no surprise, then, that the Hopkins County residents who helped the Stones may have had to cook their last farm hen to eat.

- “The Stones were one of many families to flee from war lines to the safety of Texas. Here, even though federal invasion repeatedly threatened, only a few coastal towns were under fire from the enemy.”

In fact, letters from the front of many Hopkins County boys and men who had formed up regiments showed that the did not stay close to home to fight. They went to Fredericksburg and Little Rock, but almost no documents that remain today place Hopkins County detachments within the state of Texas. Those that did stay concerned themselves with skirmishes with Comanche and Kiowa indigenous people rather than fighting union soldiers, according to a series of letters.

For this reason, those in the deep South may have viewed Texas as a safer place to seek refuge. In fact, the Oakland Cumberland Presbyterian Church located on CR 2653 between Hwy 11 and CR 4738 is the establishment of Willis and Nannie Stewart, who migrated to the area from Rising Star, Alabama when their original church was burned during the reconstruction era.

Possibly a famous pair of Hopkins County confederate refugees are the James brothers, Jesse and Frank. Originally of Missouri, the brothers either moved to or frequently visited Sulphur Springs during the reconstruction era according to a January 8, 1937 article in the News-Telegram. The famous outlaw’s cousin, George James, operated a livery stable across from the Hopkins County Echo office, the News-Telegram reported, and the brothers often came to visit friends and family while on the lam back in Missouri.

According to reports at the time (and possibly to the self-narrative of the infamous gunslingers) Jesse James and his posse sought vengeance for the Yankees who had mistreated them during the civil war, and in so doing robbed and plundered northern-owned farms.

According to the 1937 article, however, the James brothers “never strayed from the straight and narrow while using Sulphur Springs as a haven” and described them as peaceful and likeable.

- “Like most refugees, the Stones, when they visited in Hopkins County, were heartbroken over the loss of their old home to the enemy. In Texas they endured poverty, loneliness and sorrow at the deaths of two sons lost in the war. They had to lease farmland to support the family and 90 slaves dependent upon them.”

The biggest question surrounding the Civil War is the question that started it: that “all persons held as slaves within any State… shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free,” according to the Emancipation Proclamation. An 1864 tax roll of Hopkins County showed that the value of a slave was approximately $700 to $1200 each, so the Stone family was hardly destitute if they had 90 slaves– a value upwards of $63,000 in those days, which is approximately $1.8 million today.

“Money was easily obtained obtained when one could put a slave up for collateral,” Tuck writes. A large slave holder would rent out his slaves to a farmer who was unable to buy slaves. Perhaps this is what the leasing of farmland refers to on the historical marker.

The slave trade was booming in Hopkins County during the Civil War, as many “felt it was safer to have their slaves in Texas” due to the fact that Texas was far away from major battles of the war, Tuck writes. Hopkins County slaveholders often had more

“Their young boys, at one time, carried pistols for safety when school mates resented their strange manners. Yet eventually they and most other refugees were grateful to Texas for its many generosities.”

By Taylor Nye

[adning id=”33097″]