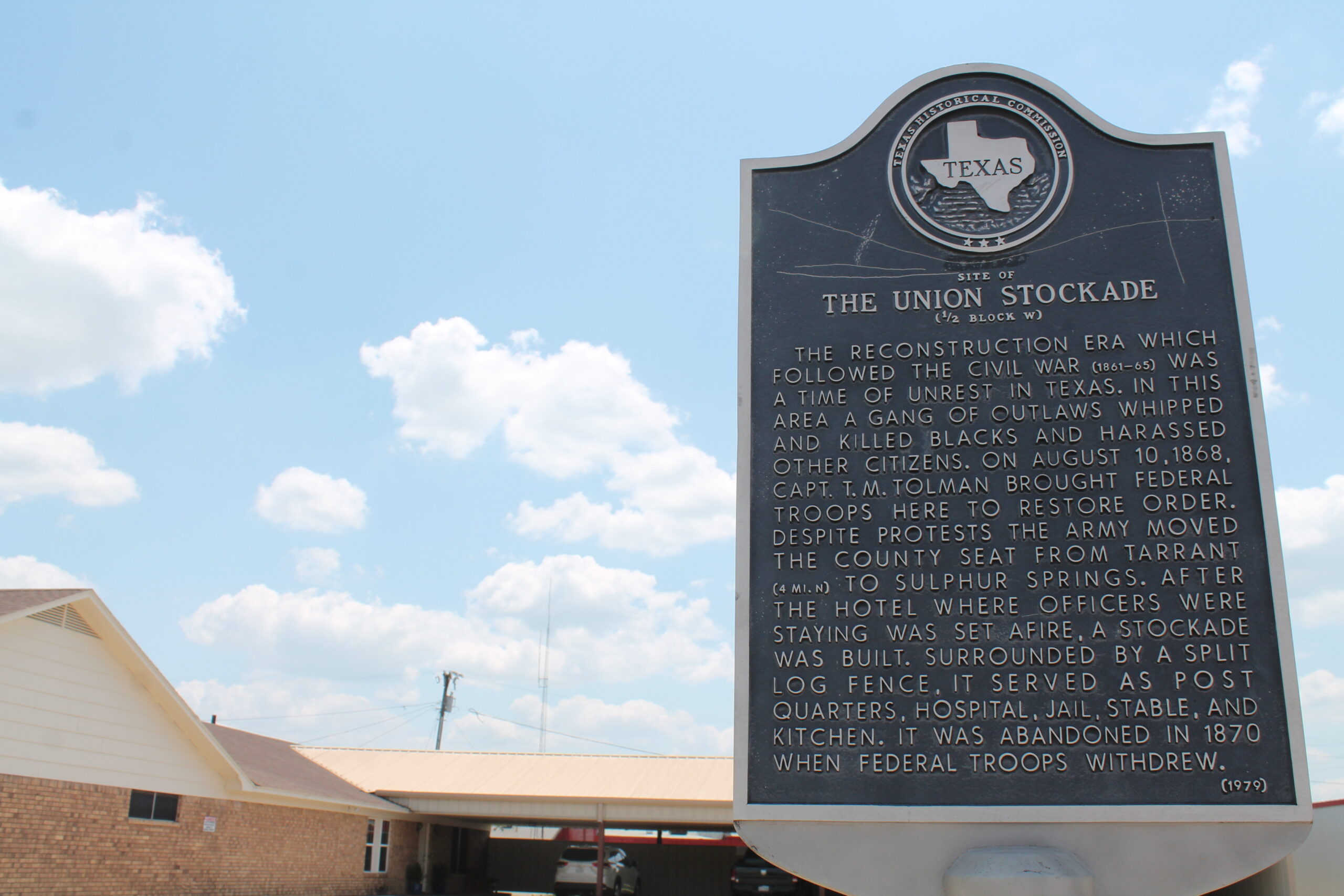

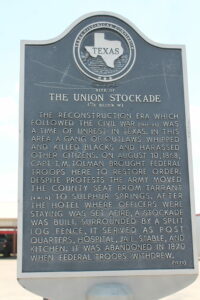

History of the Union Stockade

Often-forgotten historical marker celebrates conflicted reconstruction history; Union soldiers lived at stockade after Klan members burned hotel

[adning id=”33097″]

Although Hopkins County now is a law-abiding place, during the reconstruction era post Civil war, it was much more rough and tumble, according to historical documents.

The Civil War ended on April 9, 1865, and Texans fought their last Civil War battle on May 12, 1865 and declared the end of slavery in Texas on June 19, 1865. However, according to Hopkins County historian June Tuck, it did not “sit well” with the slaveholders of our county that they might have to abide by the laws of the U.S. government and free their slaves.

“Even though most of the slaveholders in our county turned their slaves loose, a few did not until the U.S. government showed it would be done,” Tuck wrote. “The slaves that left the farms… were not safe. Many were hunted, whipped, and killed.”

To quell unrest fomenting in Hopkins County, the union sent a regiment of troops on August 10, 1868, three years after the war had ended, to take up residence in Sulphur Springs. Initially, they resided at a hotel, although Tuck was not able to determine which of the town’s two hotels they stayed at.

On August 14, 1868, a skirmish between Union soldiers and Hopkins County “troublemakers” left two union officers dead. The union detail marched out four miles from town to investigate reports of a black woman being whipped by a particular group of men named Bickerstaff, Baker, Farrar, and Lee, when they were ambushed by these same men. This, Tuck writes, was the start of an intense and troubling period of guerilla fighting between the two sides.

Union men, according to Tuck, traveled as much as 100 miles from Sulphur Springs, sometimes by foot, to investigate reports of beatings, whippings and murders of black Americans. “The Ku Klux Klan also caused a share of trouble,” she writes, “the murder of [African Americans] is so common as to render it impossible to keep an accurate account.”

Some citizens found themselves harassed as well by the actions of the Klan, Tuck writes. They provided horses and food supply to Union soldiers, worked jobs for the Union army and formed a Citizens Fire Patrol to enforce Union laws.

Others, however, found the federal government encroaching, Tuck says. No persons were allowed to carry firearms other than soldiers or employees of the government, and no “suspicious parties” were to be “lurking” around town after 8 p.m. After saloon keepers allegedly took to getting Union soldiers drunk, “any liquor sold in quantities of more than one ordinary size bottle” whether at a grocery or bar-room could be subject to arrest and fine.

These tensions came to a head when sometime before September, 1868, the hotel that the Union soldiers and their wives were staying at was set on fire, Tuck states.

On September 29, 1868, plans for a stockade to house the Union soldiers were commissioned. Constructed of a split log fence, they rented a lot. It is now marked across from Sulphur Springs City Hall’s back parking lot and bounded Atkins, Mulberry, North Davis, and Connally Streets.

From October 21, 1868 onward, Union soldiers practiced drills, ate, and had their hospital, jail and stable at the stockade. Sleeping in tents, during the winter they often became cold and fell ill, Tuck writes.

Union soldiers packed up and moved on July 1, 1870, but were responsible for many changes in Hopkins County, according to Tuck. The previous seat of Hopkins County was the now-abandoned town of Tarrant, near Weaver, founded by Eldridge Hopkins. Union soldiers chose Sulphur Springs as the new county seat because of its easy access to water, the springs.

Sulphur Springs is now a beautiful and peaceful place to call home, but remembering the location where Union soldiers set up to reestablish law and order reminds us that reunification of the country wasn’t always a smooth process, especially in a place that counts itself so individualistic as Texas.

By Taylor Nye

[adning id=”33097″]