History of Cumby/ BlackJack Grove

From indigenous camp to stagecoach stopover: A brief history of Black Jack Grove (aka Cumby). Teetotaling, fiddling and banking were the town’s past

[adning id=”33097″]

Although it is common to think of Hopkins County as having begun in the 1840s when the first frontiersmen arrived, indigenous peoples called Northeast Texas home long before covered wagons ever left their wheel tracks in the fertile black earth. One such place was Black Jack Grove, now known as Cumby, which was an indigenous camping ground for “many years” according to Hopkins County historian Lajuana Parmalee.

The Black Jack tree, also known as the Blackjack Oak or Quercus marilandica, is a water oak species whose wood is heavy, strong and good for making firewood, posts and charcoal, according to the Texas A&M Forest Service.

Both early white settlers and indigenous people may have believed the same thing, Parmalee writes: the grove was located at “the highest elevation above sea level in Hopkins County.” The presence of the trees would indicate that, given that Black Jacks often grow in well-drained and sandy soil where other trees will not thrive, according to the Forest Service.

Modern topography confirms what historical wisdom held: Hopkins County’s highest point actually does rest in Cumby, according to Navigation Vertical Datum maps.

Throughout the early 1830s, Black Jack Grove was entirely an indigenous area, Parmalee writes. However, in 1838, Republic of Texas Rangers made their first foray into the area to use the grove of trees as a camping site, according to documents. In 1839, a group of what were reportedly Comanche indigenous people passed by present-day Mount Vernon and allegedly “murdered and scalped [the Ripley] family,” although Hämäläinen writes in “The Comanche Empire” that it was more likely the Caddo indigenous people who Rangers came into contact with at this time in East Texas, not the Commanche.

Stationed near Daingerfield, Texas Rangers decided to pursue the indigenous people, and camped near the grove of Black Jack trees, Parmalee writes. While they were there, a trooper became sick and died, and was buried in the woods to the north of their camp. The grave now sits at the north corner of Cumby’s present-day cemetery.

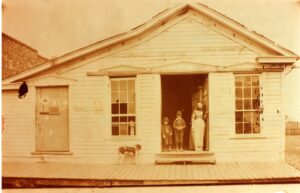

In 1849, white settlers to the area started to arrive, including town matriarch Elizabeth “Eliza” Wren, Parmalee says. In 1851, Wren sold 316 acres, nicknamed “Patent 788” to a one G.C. Roberts, which became the present business section of Cumby at the north end of today’s Main Street.

The first stores in Black Jack Grove appeared in 1851 and 1852 on the hill near the old camp ground. A clapboard tavern and hotel and an ox-driven mill gave way for a steam driven mill in 1867 and two doctors and a merchant shortly thereafter.

When the Civil War started, Black Jack Grove was directly involved, as it raised a military force known as Company K, Ninth Texas Infantry. They called their flag the Texana Trimble, Parmalee says, and although many young men left to fight, not many returned.

Although the first official post office was established in 1848 by John W. Matthews, he kept the post office at his home and only delivered mail once per week, Parmalee wrote. In 1855 the new postmaster, James Brown, convinced the US government to change the town’s name to “Theodosia,” after a book he had read and taken a liking to, according to Parmalee. Changing the town’s name caused “a bit of agitation,” Parmalee wrote, so by 1858 the name was changed back to Black Jack Grove.

However, in 1896 it became clear that there were two Texas towns with the name “Black Jack Grove,” and each of them had a post office. The citizens reluctantly allowed the name of the town to be changed to Cumby, Parmalee said, after local politician and former Confederate general Robert Cumby. Ironically, Cumby lived and died in Sulphur Springs and never resided in the town named after him, according to records. There is, however, more than one account, according to both the Dallas Morning News and Parmalee’s writings, that Sam Houston would frequently stop into town.

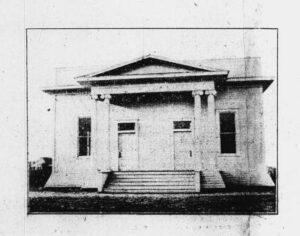

Cumby was officially incorporated on May 13, 1911, with 86 votes in favor of incorporation and 44 against, according to records. The 1920 census for Cumby listed 1100 residents “the Chamber of Commerce is waging a [sic] active campaign and is confident that a gradual growth will be shown from now on,” the Dallas Morning News wrote. Sadly, the Chamber was not effective some 100 years later, as Cumby’s 2019 population is recorded at 790.

Two things that made Cumby special in the 1920s and 1930s, the Dallas Morning News noted, were the town’s dedication to fiddling and prohibition. The town became a mecca for fiddlers, who penned a song based on the previous name, “Black Jack Grove.” Catalogued by the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center and viewable now by skilled fiddlers on YouTube, the only words to the song are “Black Jack Grove.”

The Dallas Morning News hailed Cumby as one of the first towns to instate prohibition, describing the women of the area as the “went on the rampage.”

“Both places [saloons] were sacked and the chocolate loam soil got a good jag from whisky, gin, and beer which splashed out from breaking bottles. Since that time, so it is claimed, Cumby has been bone-dry except for the rains from Heaven,” the paper said.

As the 1970s and 1980s came, Cumby found that it would “remain a small town” as Interstate 69 bypassed the town as it wove its way from Greenville to Sulphur Springs, according to Parmalee. Although Cumby is no longer a Northeast Texas trading center, it is still of vital importance to those who call it home. Every year the town hosts a Black Jack festival to honor the original town’s name.

In March 2022, a citizen named Anna Duckworth petitioned to have the town’s name changed back to BlackJack Grove, and was met with anger from other townsfolk. She immediately withdrew her request.

By Taylor Nye

[adning id=”33097″]