The Care and Feeding of Post Oaks : The Royal Post Oak by Mario Villarino

[adning id=”33097″]

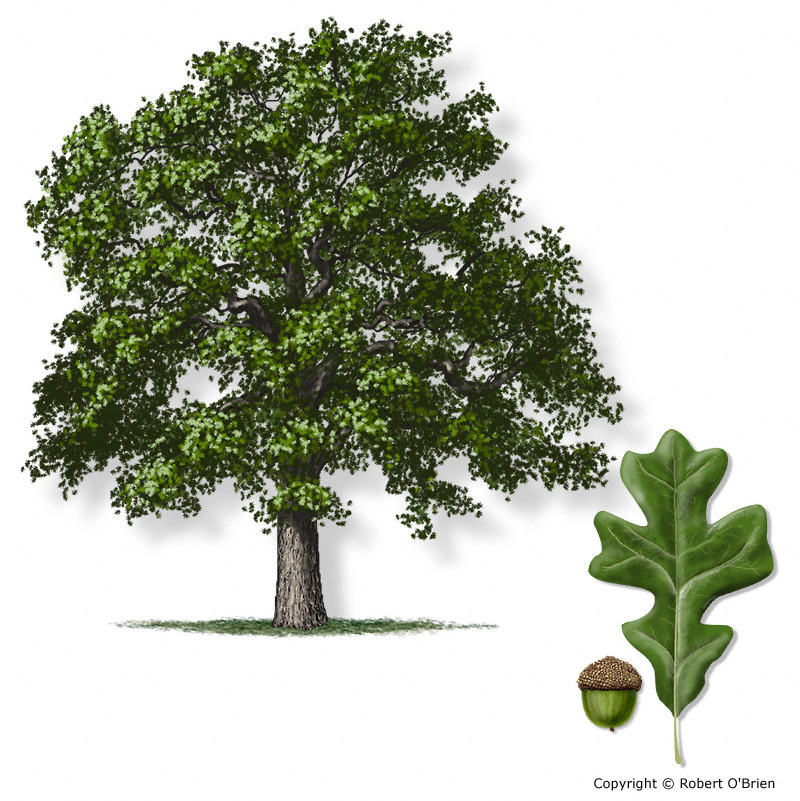

Post oaks are the crowning achievement of the plant kingdom in the Cross Timbers geographical region of Texas. Post oaks are highly adapted to our soils and climate. Post oaks however, have a well-deserved reputation for succumbing to the stresses of “urban blight”. This tree simply cannot stand root disturbance. When a property is purchased for development and a decision is made to preserve post oak trees at least one-half of the root system must be left undisturbed. Tree roots are not as deep as most people think. The roots that do the actual work of absorbing water and minerals are located in the topsoil. Through the ages, our native oaks have endured the extreme weather conditions of North Texas. In their natural state, post oak roots are covered by several layers of fallen leaves and rich leaf compost. We strip all that off and grow turfgrasses over their roots, which aggressively compete with tree roots for available water and nutrients. Suddenly they are no longer in a natural state. They are out of their element, so to speak. It is better to grow ground covers, such as English ivy and Vinca, rather than turf under trees. This allows you to water less and allows the leaves to fall and nestle into the groundcover creating the natural leaf litter mulch to which they are accustomed and adapted. Post oaks and blackjack oaks are among the last trees to leaf out in our area. They are also among the earliest to finish growing each spring. Fertilizing your native oaks early will help them take better advantage of their short growing season by putting on more leaves and making each leaf bigger. Use a balanced fertilizer on mature trees. High nitrogen fertilizers may stimulate excessive growth, thereby depleting reserves on already weakened trees. Broadcast five pounds of 15-5-10 or equivalent fertilizer per 1,000 square feet of effective rooting area in at budbreak and repeat the application every six weeks as long as new growth is flushing out at the shoot tips. Because native oaks in developed home sites and businesses are already under stress, additional stress from insects and diseases can sometimes be fatal. Making periodic inspections of folliage for signs of insects and diseases throughout the growing season will often help you spot a problem before serious harm is done. Scheduling plant bug sprays for the following spring is advised for trees showing significant damage in the current year. Use insecticides containing carbaryl, such as Sevin®, or acephate, such as Orthene® for control. Our native oaks possess an inherent will to live and will do their best to survive whatever circumstances they encounter. Except for oak wilt which does not attack post oaks, there is no single disease that takes our native oaks out and there is no magic pill that will restore their health. They are subject to the vicissitudes of life and must struggle to overcome them, preferably with our assistance rather than our antagonism. Following the initial trauma of construction and landscape establishment, tree health and vigor must be restored, slowly, over time, by the tree itself gathering strength. For all the worry they cause, our native oaks are among our most beautiful, plentiful and long-lived trees. By exercising caution during construction, watching our watering habits, making timely applications of fertilizer or well-rotted compost, and spraying for insects and diseases when necessary, our native oak forest will persist for generations to come. When we develop a new oak forest for housing we tend most often to remove the young trees and leave the large, mature oaks. All living things have a life span and many of the mature oaks we select are actually entering old age when their life span may not be too far from running out. As trees reach maturity and old age their canopies tend to flatten out on top and they grow more broad than tall. Crowded trees, of course, do not spread out but simply expire, and at an earlier age. As trees grow and crowd together the canopies of some trees are gradually over-crowned and closed off from light. These trees should be removed when it is apparent these trees are becoming weak from shading. Removing weak, over-crowned trees will allow the canopy of the remaining tree to broaden and enlarge which naturally makes them stronger and healthier in the long run. In the natural setting young trees replace old trees as they die. All trees, even oaks eventually die. Since we do not have young trees coming up through the forest floor to replace the aged and dying, we need to plant new trees to take their place. The single best replacement tree for our native oaks is the bur oak. Of the trees in the commercial trade the bur oak is in every respect the closest in form and habit to the post oak itself but, contrary to the post oak, is one of the fastest growing trees we can plant. Other desirable shade trees suitable for planting are bur oak, live oak, shumard oak, chinquapin oak, pecan, bald cypress, cedar elm, lacebark elm, Texas ash, fruitless cultivars of osage orange and Chinese pistache. The information given herein is for educational purposes only. Reference to commercial products or trade names is made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement by the Cooperative Extension Service is implied. Extension programs serve people of all ages regardless of socioeconomic level, race, color, sex, religion, disability, or national origin. The Texas A&M University System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the County Commissioners Courts of Texas Cooperating.

[adning id=”33207″]

[pro_ad_display_adzone id=”25296″]

[adning id=”33207″]